This student-led project, through the Geography Graduate Student Association (GGSA) took place Monday, April 10th, 2023 from 3-6 PM in the Aztec Student Union Theatre with a reception on the Aztec Student Union Terrace (3rd floor) from 6-8 PM. The symposium focused on bringing together Indigenous leaders and traditional practitioners to provide much-needed perspectives, practices, and wisdom–and the associated challenges Indigenous communities may be facing–related to colonial- and industrial-induced climate change. The purpose is twofold: (1) to provide a forum for Indigenous insights, concerns, and lessons to challenge blind-spots, errors, and exclusions of Western climate science, and (2) to present SDSU students, faculty, staff, alumni, and the wider public with opportunities to become worthy to responding to these challenges

Post-event newsletter

Watch the recording

Add this event to your calendar

Click the button below to add this event to your google calendar:

Can’t attend in person? Register via Zoom

Click the button below to register via zoom. Although this event is meant to occur in person, we understand that not all are able to do so. This will be a hybrid event!

Schedule

Symposium

Date: Monday, April 10th, 2023

Time: 3-6 PM

Location: Aztec Student Union Theatre (second level)

Moderators:

Dr. Shasta Gaughen (Environmental Director)

Dr. Giorgio Hadi Curti (Socio-Cultural Geographer)

Speakers:

Michael Connolly Miskwish (The Kumeyaay Nation)

Edward Wemytewa (The Zuni Tribe)

Dr. Ora Marek-Martinez (The Navajo Nation)

Tino Villaluz (The Swinomish Tribe)

Daranda Hinkey (The Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe)

Reception

Date: Monday, April 10th, 2023

Time: 6-8 PM

Location: Aztec Student Union Third Level Terrace (North ‘Arcade’ in the floor plan below)

Food: Charcuterie Board (gouda, st. angel, brie cheese, salami, crackers, dried apricot, fruit); Seasonal Fruit Platter; Hummus & Pita; Salad & Rolls

Dessert (limited supply): Chocolate Brownies; Cheesecake

Beverages: Iced Water; Hot Tea; Coffee

Please refer to the Student Union floor plan below:

Directions to the Aztec Student Union

Curious about other methods of commuting and transportation?

Click on the button below to explore your options:

Need a parking pass for this event?

Please fill out the following google form by clicking the button below:

Kumeyaay Land Acknowledgment

Prepared by Dr. Giorgio Hadi Curti

Since time immemorial, the Kumeyaay people—Ipai to the north, Tipai to the south, Kamia to the inland, and all of those who have used and continue to use the self-identifier, Diegueno, whether by active choice or colonial imposition—have been a part of the lands and waters we often call today, San Diego County.

These lands and waters have nourished, healed, protected, and been intimate and indelible parts of the familial and social of Kumeyaay for many, many generations—and continue to be today. With, in, of, and through these lands and waters, Kumeyaay have practiced familial and social relationships of stewardship, care, balance, and harmony—relational practices that live and support life always for the people.

What I have been taught by the Kumeyaay people with and for whom I work is that the depth and weight of what it means for an act, a thought, a song, a prayer, a method, an offering, an action, a practice to be for the people can only truly be glimpsed and loosely grasped when notions of “the person” and concepts of “the social” are opened up to relations and capacities that exist far before and far beyond dominant and dominating humancentric errors and blinders.

As members of the San Diego State University community and residents of the City and County of San Diego, it is imperative that those of us who are not Indigenous to these lands and waters recognize that we are contributing to a settler colonial institution, that we are, ourselves, settlers in Indigenous Kumeyaay lands, and that more often than not we are directly implicated in promulgating, promoting, and perpetuating these dominant and dominating errors and blinders—whether passively or actively.

We must both acknowledge this legacy and ongoing presence of coloniality and take ownership of the fact that each one of us has a deep obligation and weighted responsibility to actively and productively work towards restorative geographical, historical, political, cognitive, legal, educational, and social justice with and for Kumeyaay people—wherever, whenever, and however they deem appropriate.

It is thus essential that the language of land acknowledgments not be confused for the production of spaces for equitable and corrective action, or those of representational recognition mistaken for productive systemic change. If acknowledgments are to be meaningful they must be continually generative—therefore so, too, must they be accompanied by actionable institutional respect and operational structural inclusion—in perspective, policy, practice, return, and restoration—of the knowledge and political sovereignty of Kumeyaay people—and, indeed, all Native peoples—to all ancestral and familial lands and waters.

On January 20, 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 13985 on “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities through the Federal Government.” The Pueblo of Zuni responded with a government-to-government consultation letter to the Biden-Harris Administration and Office of Management and Budget on July 1, 2021, in part stating:

All lands and waters within and intersecting the borders and boundaries of the United States are Native lands and waters (see https://native-land.ca/). This basic fact must first formally be addressed, officially recognized, operationally accounted for, and serve as the basis of any honest and sincere effort at advancing equity and support for the underserved A:shiwi community and Pueblo of Zuni [and, indeed, all Native American Tribes and communities]. Recalling your own recent words this past June Mr. President, “Great nations don’t ignore their most painful moments. They don’t ignore those moments of the past. They embrace them. Great nations don’t walk away. We come to terms with the mistakes we made.”

These mistakes of settler colonial nations are as deep as they are enduring, and as prevalent as they are dispossessing and alienating—globally and locally, yesterday and today. As Potawatomi climate and environmental justice scholar Kyle Whyte has explained, Colonial- and industrial-induced climate change is in fact just one intensive manifestation of environmental change born of settler colonial societies:

Thinking about climate injustice against Indigenous peoples is less about envisioning a new future and more like the experience of déjà vu. This is because climate injustice is part of a cyclical history situated within the larger struggle of anthropogenic environmental change catalysed by colonialism, industrialism and capitalism—not three unfortunately converging courses of history [Whyte 2016:16].

Flowing through the heart and enveloping the mind of colonial, industrial, and capitalistic actors and their judgements, values, perspectives, choices, politics, and practices driving climate change are what English anthropologist Gregory Bateson identified 50 years ago as “epistemological fallacies” and “errors” of dominant—and dominating—Western systems of logic and value. Quoting Bateson:

[T]he last hundred years have demonstrated empirically that if an organism or aggregate of organisms sets to work with a focus on its own survival and thinks that that is the way to select its adaptive moves, its “progress” ends up with a destroyed environment. If the organism ends up destroying its environment, it has in fact destroyed itself [Bateson 1987:457].

And:

[Such] [e]pistemological error is all right, it’s fine, up to the point at which you create around your-self a universe in which that error becomes immanent in monstrous changes of the universe that you have created and now try to live in [Bateson 1987:485].

These epistemological fallacies and errors inform and guide not only how we frame the possible futures that climate change may or may not bring, but limit what may be included of various pasts. Mathews and Barnes address this in their introduction to an important 2016 special issue of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. They note:

[J]ust as states have sought to manipulate the past by celebrating some moments in history and silencing others, so, too, they have linked these selected pasts to particular futures. The question of the past, then, if looked at in the right way, has always also been a question about the future….

The future can be told as a story, calculated as a probability, or speculated upon as a form of potentially valuable risk…. The future … is not one but many, and those who create futures typically seek to narrow down what the future can be to a relatively limited subset of possible registers [Mathews and Barnes 2016:10-11].

I have been taught by Kumeeyaay and A:shiwi, ‘Atáaxum and Diné, Coast Salish and Chalá∙at, Lakota and Dakota, Paiute and Shoshone that to truly acknowledge Indigenous lands and waters is also to always recognize, honor, and respect both the futures and pasts of non-human and more-than-human relations that have existed from the times of the beginning of the beginning or the beginning with no beginning; these are the relationships of the air and the winds; the mists and the clouds; the soils and the minerals; the animals and the plants; the stars and the constellations—what is below and what is above. This is the life of land, air, and water. This is the capacitational life that Colonial- and industrial-induced climate change monstrously effaces and eviscerates.

Anishnaabe experience and wisdom have identified how “‘invasive’ ideologies” of settler colonial societies often manifest in and as “invasive land ethic[s]” (Reo and Ogden 2018). We can term these mutual manifestations “invasive species of thought” (Wemytewa, Curti, and Dongoske 2023 and in progress) in order to better amplify recognition and more fully name the implications of how they function in and as ongoing manifolding processes of thought and action that exceedingly work in the interests of sustaining privilege for some and perpetuating the destruction, dispossession, marginalization, and alienation of many, many others.

An etymological excavation of the term “species” reveals its root to be the Latin specere, an inflection of specio, meaning to “observe,” “watch,” or “look at.” As this suggests, considerations of what species are exist as culturally imbued constructions cataloguing, categorizing, and classifying complex formational differences of the life of the world. Where and when such categorizational schemes become invasive is in their deployments that confuse abstractions and fictions of understanding for a singular Reality beholden to narrow and limited Western notions of valid knowledge production, linear time, geometrized space, and their attendant economic, developmental, and capitalistic values that reify and rationalize devastation of places, land- and water-scapes, social relationships of reciprocity, and capacities for health and wellbeing for a multitude of peoples—human, non-human, and more-than-human alike. These are the invasive species of thought and action that have brought to all of us—and brought all of us to—the increasing effects of industrial- and colonial-induced climate change.

Kyle Whyte and South Asian environmentalist Claude Alvares have each respectively identified how, “[a]s an environmental injustice, settler colonialism is a social process by which at least one society seeks to establish its own collective continuance at the expense of the collective continuance of one or more other societies” (Whyte 2018:136), and “Western science, [as] an associate of colonial power, … function[s] not any less brazenly and effectively: extending its hegemony by intimidation, propaganda, catechism and political force” (Alvares 2010:244). With today’s Climate Talks, we seek to perform a double movement of (re)turning the gaze on these invasive species and their processes of thought, action, and inaction while offering productive pathways to enter into restorative and just correctives of and for relational life and relational life/way systems.

Goenpul scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) has identified how Indigenous pasts and futures and the relational life/ways intimately and indelibly enfolding and enfolded by them are constrained and imposed upon by settler colonial gazes of social and governmental “white possessive logics.” She explains how these racialized logics manifest and function as:

unearned invisible assets that benefit white people in their everyday lives; they are possessions. These assets include simple things such as not having to educate white children about systemic racism for their protection and having white identity affirmed in society on a daily basis through positive representations in the media, government policies, legislation, and the education system…. Assets such as these are derived from and contribute to the normalization of white possessiveness, which remains invisible to white people in everyday practice [Moreton-Robinson 2015:97].

Within, through, and beyond mainstream Western climate policy and governance, white possessive logics and their unearned privileges are invasively “operationalized within discourses to circulate sets of meanings about ownership of the nation, as part of commonsense knowledge, decision making, and socially produced conventions” and “underpinned by an excessive desire to invest in reproducing and reaffirming the nation-state’s ownership, control, and domination” (Moreton-Robinson 2015:xii).

Through misplaced confidence in highly partial knowledge schemes built through methodologies that pretend they have no foundational philosophies and their white possessive couplings to an “ideology of manifest destiny [that] continues to be fuelled [sic] by a sense of entitled racial and religious superiority maintained through networks and relations of power and privilege” (Styres 2017:93-84), various manifestations of settler colonial domination endure through mainstream climate science policy and practice as an associate to colonial power to elide considerations and undermine capacities of and for resilience and collective continuance of Indigenous peoples. The epistemological and ontological grounding of these white possessive logics is one that continually “separates and isolates and mistakes labeling and identification for knowledge” (Deloria and Wildcat 2001:133) and “superimpose[s] on nature … a [mathematical and geometrical] grid … like the land survey system…. These units, in turn, are used as the basis for dealing with the land, but they are not part of the nature of the land” (Little Bear 2000:ix). While the invasive racialized logics and species of thought underpinning these enduring injustices are omnipresent in settler colonial societies, their operations are often concomitantly unidentified and unnamed in both their settler colonial governmental and academic possessive deployments (Moreton-Robinson 2015:xxiii).

When promulgating, promoting, and perpetuating epistemological errors driving climate change, and the invasive species of thought attempting to address sustainability through unsustainable epistemologies and valuations, our institutions become perverse—and when enabling these institutional and structural monstrosities—whether passively or actively—we ourselves become monstrous. This is perhaps why in 2020 McGregor et al. took the position that:

Indigenous environmental justice (IEJ) is required in order to address [both] the challenges of the ecological crisis as well the various forms of violence and injustices experienced specifically by Indigenous peoples. This must be grounded in Indigenous philosophies, ontologies, and epistemologies in order to reflect Indigenous conceptions of what constitutes justice [McGregor et al. 2020:35].

The lesson then—if we are to become worthy to the challenges of today’s Climate Talks—is to begin to come to know, from the deep time and deep space knowledges, sciences, and wisdoms that formed and grew together with the lands and waters of what we often call today “the United States of America”, how to start to find just pathways to (re)build circuits for correctives to the epistemological errors and invasive species of thought that continue to drive our dominant modes of knowledge production, evaluation, and valuation—of pasts and futures; scientific, philosophical, economic, or otherwise—to become less monstrous in thought and action. You, the audience, are the future climate scientists and the present and future decision-makers. There are many more possibilities for inclusive, productive, balanced, collective, restorative, and generative pasts and futures out there for the people than what your algorithms, models, and projections commonly tell.

Get to know our moderators!

Dr. Shasta Gaughen

Shasta Gaughen is the Environmental Director and the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Pala Band of Mission Indians in Payómkawichum (Luiseño) territory in what is now called San Diego County, California. She has worked for Pala since January 2005, and established Pala’s Tribal Historic Preservation Office in 2008. Dr. Gaughen received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of New Mexico in 2011 and a Master of Legal Studies in Indigenous Peoples Law from the University of Oklahoma College of Law in 2021. She taught for the Department of Anthropology at California State University, San Marcos, from 2006-2019. She is Chair of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers, a member of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Vice President of the Board for the Native American Environmental Protection Coalition, and a member of the Institute of Tribal Environmental Professionals’ Climate Change Advisory Committee. Dr. Gaughen oversees the Tribal Climate Health Project, a grant-funded education and outreach project that includes a website, resource clearinghouse, webinars, videos, and in-person presentations on climate change and health adaptation in Tribal communities.

Contact Shasta:

760-891-3515

Dr. Giorgio Hadi Curti

Giorgio is a socio-cultural geographer and critical ethnographer who works at the intersections of cultural and natural resources laws, traditional and local knowledges and sciences, and the collaborative development and implementation of land and water stewardship and management strategies guided and defined by Indigenous and traditional communities and associated human-environment relationships and worldview and value systems. Giorgio received his PhD in 2010 from the San Diego State University-University of California, Santa Barbara Geography Joint Doctoral Program. In 2016, Giorgio and friend and fellow SDSU-UCSB Joint Doctoral alum, Christopher Moreno, founded Cultural Geographics Consulting (CGC), a minority-owned small business that pursues ontological and epistemic justice in its dedicated mission to help create a world where historically and geographically marginalized peoples are empowered to define and direct their own futures. In addition to his work with CGC, Giorgio serves as Adjunct Professor and sometimes-Lecturer in the SDSU Department of Geography, and as a Research Associate with the Young People’s Environments, Society and Space Research Center.

Get to know our speakers!

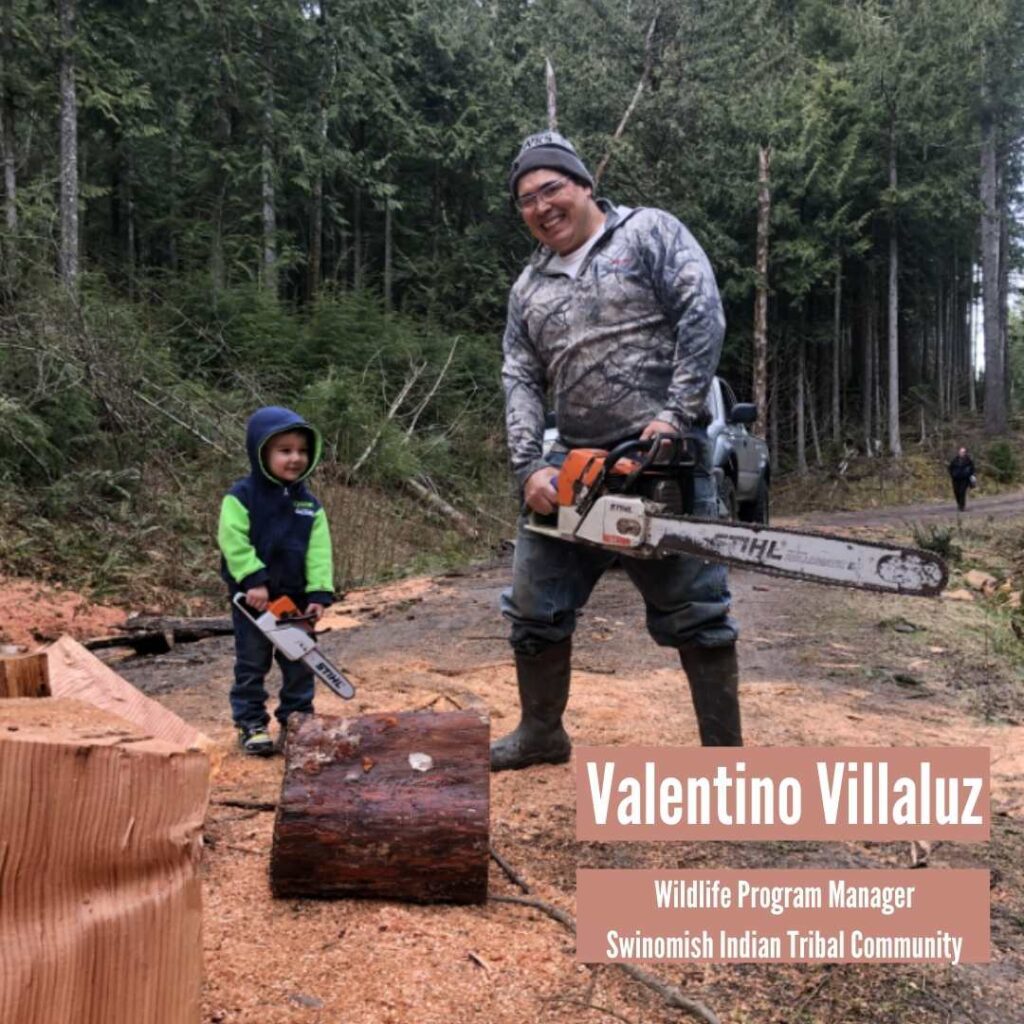

Valentino (Tino) Villaluz

Wildlife Program Manager, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

I am a Swinomish Tribal member. Lifelong practitioner of nature-based worship as well as one of the primary first foods providers for my community. I have been, and continue to be a student of my culture and heritage. I have no formal western education beyond high school. My career path has varied greatly ranging from the Bering sea to senior management in the casino industry, and now serving my community in a natural resources policy position mostly on the terrestrial side. My current service is one of accountability, reflection, and a future generational focus on natural(cultural) resources. I have spent the majority of my life trying to listen and not speak however have been transitioning into a speaking role being mentored by a cultural leader and father figure Chester Cayou. When I’m not in meetings or bound to the office I own and operate a treaty fishing and crabbing boat for both subsistence and economics.

The photos are me taking a work meeting while on the Salish sea, cutting wood for elders and crabbing with my daughter

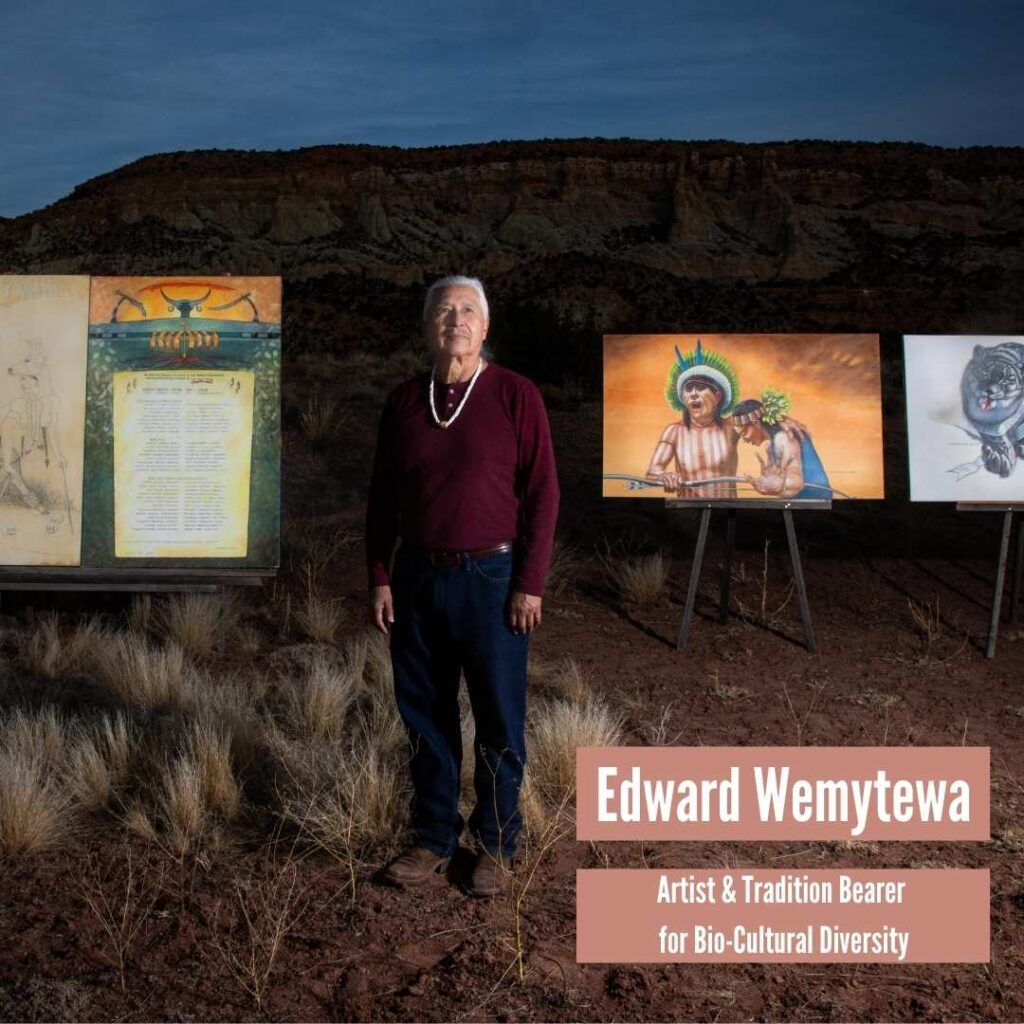

Edward Wemytewa

Artist & Tradition Bearer for Biocultural Diversity

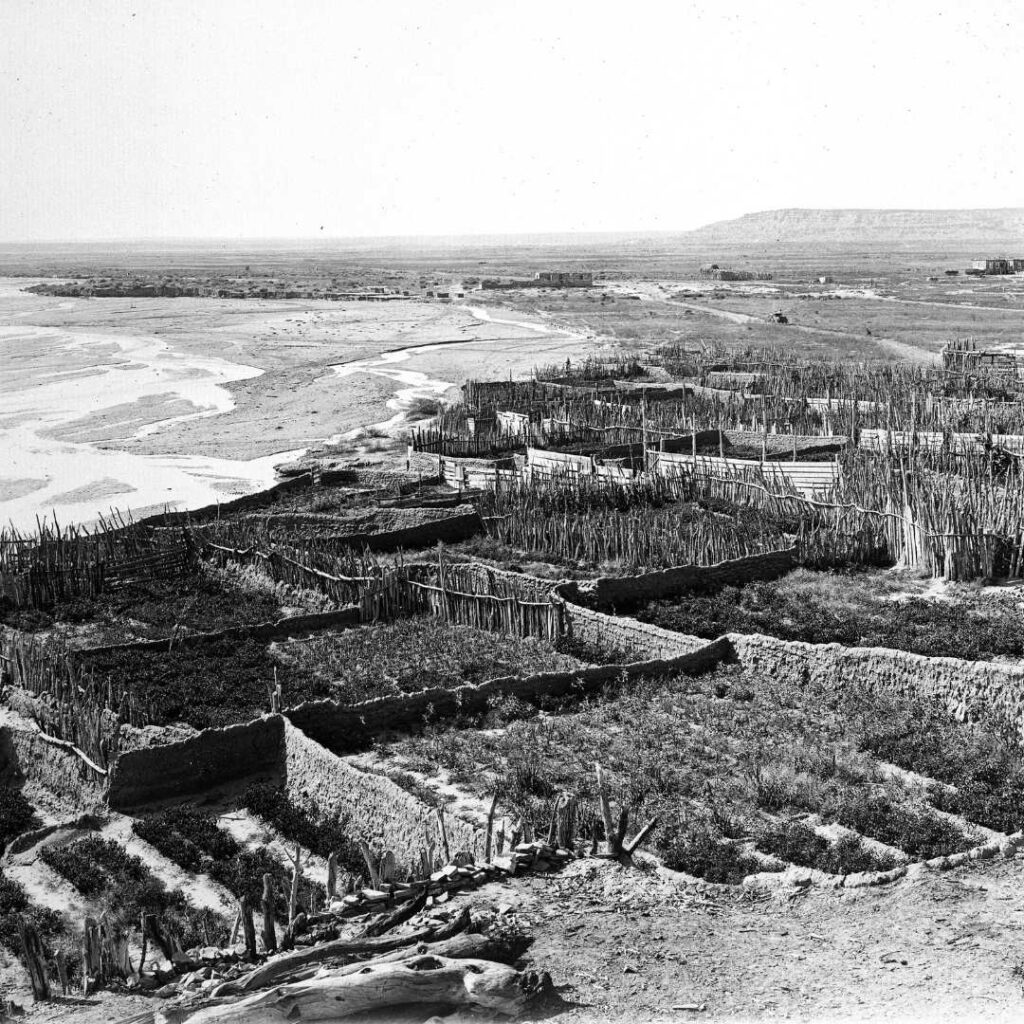

Description of photos: I am posing with the “Anthropocene” mural, 2) two slides of the Zuni River [Circa 1879; Credit the Smithsonian archives for the old photographs], and 3) a “cultural map of the immediate Zuni waterways” in New Mexico and Arizona. Of course, the waterways are dead, save for the few wetland sites and groundwater.

Biography:

I was born in Zuni Village, clans are “Tobacco” and “Child of Crow,” whose first language is Shiwi’ma: bena:we. I began my career as a visual artist and traditional storyteller, recording Zuni life and stories from the last traditional storytellers. In 1995, I founded the Idiwanan An Chawe (Children of the Middle Earth) Theatre, where my art evolved with the contemporary issues facing the Zuni People.

Our ancestors come from the Grand Canyon, settling in eastern Arizona/western New Mexico. Our stories from our cultural heritage speak about our roots that connect us to a place called “The Place of Everlasting Summer,” or “Olo’ik’yana Łimn’a,” a place in Mexico.

As a tribal councilman, elected two terms, beginning in 2001, my priority was fighting to protect water in Arizona and New Mexico. The Zuni River, which once flowed through our village has died. From 1998 through 2003, I sat through many hours of Water Rights negotiations and traveled to Washington DC on related matters.

Raising Indigenous Consciousness through Art 2013-2020

Art has been my passion and life. The process of “creating art” feeds my spirit, affirms my place “of being”. In the past 9 years, art has been a vehicle for raising my Indigenous voice in a larger Indigenous movement to address climate change. The Indigenous movement, for example, like “Standing Rock” in 2016 was out there. A lot of action and voices were raised, and then the COVID-19 Pandemic hit, as never been seen within our generation. Everything came to a sudden stop. So, in retrospect, it seemed my art was on the run compared to when the international community came to a scratching halt due to the pandemic. Two years ago, in April of 2020, I released a video of my art called “Art on the Run.” It captures an aspect of the Indigenous movement through an artistic lens. The video gives a glimpse of some of the pieces of art featured in an art installation, which provides for layers of voices, primarily about “Anthropocene,” that good weather is over.

Tradition Bearer for Bio-Cultural Diversity

As a Tradition Bearer, my hope is that in converging on an “obscure landscape” in the new millennium that through a conversation between Science and Philosophy provides for inclusion of Indigenous thought and cultural practice protections find its way into nation/state policies.

Indigenous Ceremony is not far removed from science. One example is in the pilgrimages to sacred sites and associated with it is the practice of collecting plant and animal “specimens,” which are then taken to the village to show as a “testament” of the state of the sacred site. In the past one hundred years this has been critical in determining the health of, or lack of, an ecological balance at Kołuwal’a, Zuni Heaven, the confluence of the Zuni River and the Little Colorado River, in Arizona. Another example is in the imagery created by the telling of a timeless prayer, which describes poetically the blossoming of the Water Cycle.

Though the A:shiwi (Zuni) have such knowledge to its natural environment, in one court case, I witnessed an arrogant attorney on the opposing side, frustrated with Zuni’s position on water rights, touted that the Zunis knew nothing about aquifers. Our attorney, an Indigenous woman herself, eloquently and firmly stated to him saying, “Zunis know everything about aquifers. They hold aquifers sacred”. We are a part of the NATURAL WORLD and its NATURAL LAWS.

Just prior to my trip to Tlaxcala, Mexico, in July 2017, I was contacted by the Zuni Cultural Resources Enterprise regarding damage to a Zuni Ancestral site named Amity Pueblo. At least 14 human remains were desecrated. Subsequently, the Arizona State Game and Fish (AZG&F) contacted me per email and set a date for my interview regarding the desecration and that my interview would become a part of a training video produced through the AZG&F. The Amity Pueblo—A Cultural Sensitivity Training Video was being produced for the agencies so they could work better together in the future. I was actually looking forward to the interview until a short time later when I saw the desecration of an ancient pyramid, which was supposedly built to honor Xicotencatl’s father at Tizatlan. Tizatlan is in the State of Tlaxcala, located east of Mexico City, and on top of a prominent hill where the vista was gorgeous. Looking southwesterly from the hill top one could see the active volcano called Popocatepetl, and the associated chain of mountains–Istacihuatl (the White Woman), La Malinche (Daughter of Cuauhtemoc/also Nahuatl name: “Matlalcueye,” meaning “Blue Skirt”), and Cuatlapango (Decapitated Head). The Tlaxacaltec temple was decapitated and a Catholic church named Capias Abierta, was constructed in its place using the very stone that embodied the pyramid’s crown. Returning from Mexico City, I emailed my contact at the AZG&F telling them I changed my mind. As of January 2020, the Amity Pueblo education video had been pending completion.

Today, nationally the Indigenous Peoples—from activists to tribal nations, to educational institutions, to state and federal agents, even the rare politicians (Indigenous and non-Indigenous)—are openly standing up on behalf of their Indigenous constituents. It is imperative that we, along with our allies push for laws protecting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples internationally and at Nation/State levels. Indigenous Peoples in the United States are central in re-defining a meaningful America and in protecting Earth Mother. Mni Wichoni, Agua es Vida, Water is Life.

Dr. Ora Marek-Martinez

Director, Native American Cultural Center

Assistant Professor, Anthropology

Dr. Ora Marek-Martinez (she/her/asdzáá/ayat) is a citizen of the Diné (Navajo) Nation, and is of the Mountain Cove clan; her father was Nez Perce from Northern Idaho. As the Director of the Native American Cultural Center, Ora’s work includes supporting and ensuring the success of Northern Arizona University Native American and Indigenous students through Indigenized programming and services to meet the unique needs of our students. As an Assistant Professor in the Northern Arizona University Anthropology Department, her research interests include Indigenous archaeology and Indigenous Heritage management, including research and approaches that utilize ancestral knowledge and storytelling in the creation of archaeological knowledge. Other research interests include southwestern archaeology, Indigenous futurisms, and decolonizing and Indigenizing archaeological narratives of the cultural landscape on Indigenous homelands as a way to reaffirm Indigenous connections to land and place. Her current research focuses on a Flagstaff Indigenous Heritage Trail project, and an ethnographic research project on Indigenous archaeology that will contribute to the efforts in our discipline to move archaeology beyond its colonial origin. Dr. Marek-Martinez is also a founding member of the Indigenous Archaeology Coalition.

Links:

- NAU Profile: https://directory.nau.edu/person/ovm

- Twitter: @DocMarek

Michael Connolly Miskwish

Campo Kumeyaay Nation

Michael is a citizen of the Campo Kumeyaay Nation. He has written extensively on tribal economics, Kumeyaay history and resource management. He has three published books on Kumeyaay history and cosmology. He has curated exhibits on Kumeyaay culture and history for the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and the Museum of Man in San Diego, California. He has done extensive work in bringing traditional ecological knowledge into modern land management practices.

Michael holds a Master of Arts in Economics from San Diego State University, a Bachelor of Science in Manufacturing Engineering from National University and an Associate of Arts in Kumeyaay Studies from Cuyamaca/Kumeyaay Community College. His work as an educator includes lecturer positions with San Diego State University and Kumeyaay Community College. He served 17 years in elected office for the Campo Kumeyaay Nation. He is currently a doctoral student at UC San Diego in Sociocultural Anthropology. He also consults with tribal governments and governmental agencies on topics of

economics, government policy, infrastructure, resource management, taxation and education. He continues to write and lecture on Kumeyaay history and culture.

Daranda Hinkey

Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Tribe

Co-founder of People of Red Mountain

Daranda is a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe and co-founder of People of Red Mountain. People of Red Mountain is a collective group of descendants of the Fort McDermitt Tribe whose role is to protect, preserve, and steward places and landscapes fundamental to tradition, knowledge, and identities as Nuwu (People) especially from harm or destruction such as Peehee Mu’huh (Thacker Pass). She graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor’s of Science in Environmental Science and Policy while playing basketball on the women’s team. She spent a year after graduation working for Lomakatsi Restoration Project in Ashland, Oregon implementing traditional ecological knowledge into land management practices and leading tribal youth workforce programs. She moved to McDermitt, Nevada, in June of 2021 after learning about the proposed Lithium Mine at Thacker Pass to be more involved in protecting sacred lands and waters. She is currently teaching science and Indigenous Studies at McDermitt High School and serves as an assistant coach for their girls’ basketball team.

A special shout-out to our planning team (pictured below) for putting this event together! Also Giorgio Hadi Curti & Kristen Monteverde for their feedback throughout this process. This event is funded by the San Diego State University Student Success Fee.

Questions? Email Corrie Monteverde at cmonteverde@sdsu.edu or leave a comment in our ‘Contact Us’ tab.