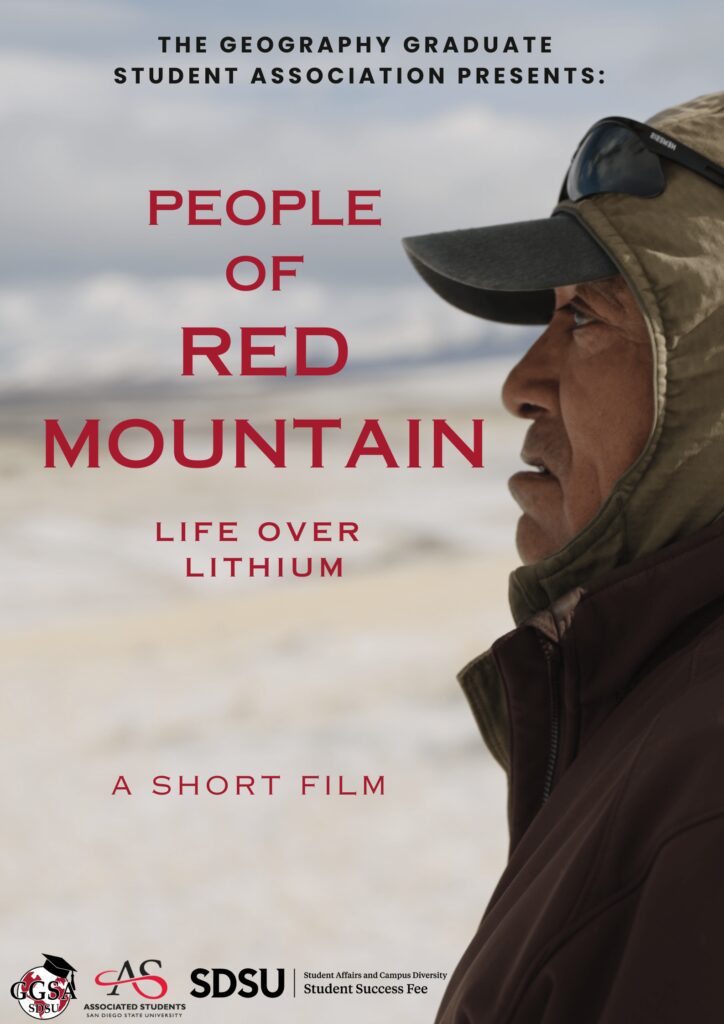

This short film screening focused on the impacts of lithium mining on the sacred lands of the People of Red Mountain occurred Thursday, April 25th, 2024, from 5 – 8 PM at SDSU’s Scripps Cottage and Patio.

Watch the film!

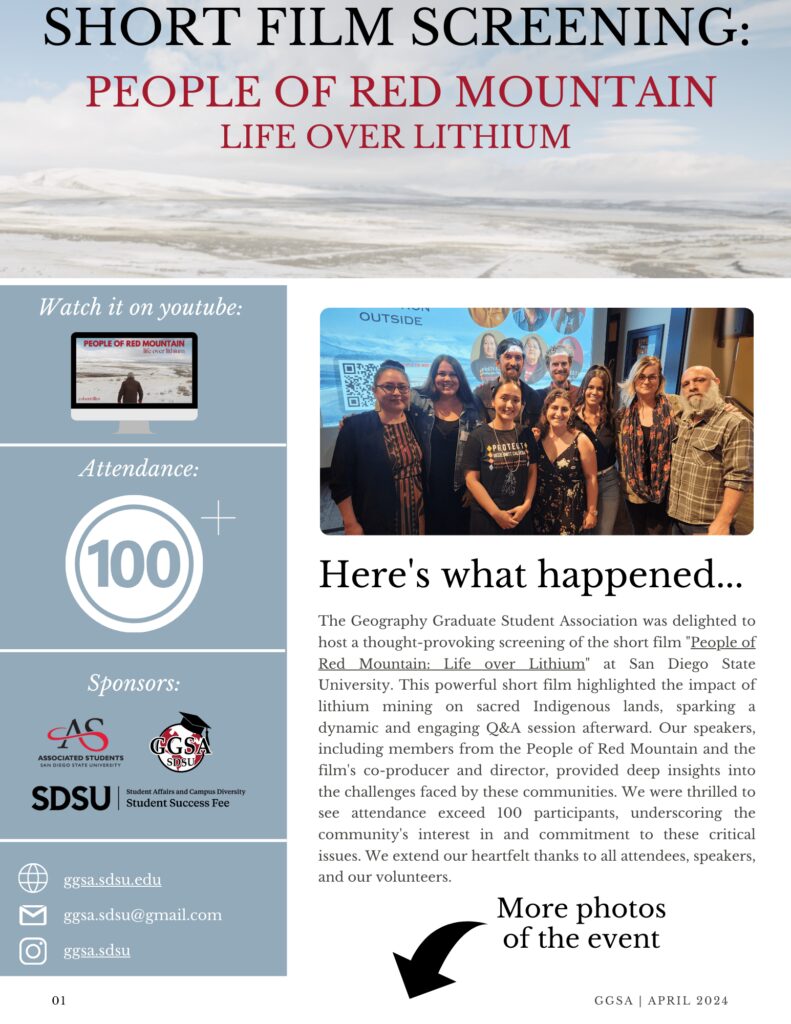

Post-event newsletter

Please read our post-event wrap-up newsletter below.

Schedule

Date: Thursday, April 25th, 2024

Screening time: 5 – 530 PM (Scripps Cottage)

Q&A: 530 – 630 PM (Scripps Cottage)

Catered Reception: 630 – 8 PM (Scripps Patio)

Speakers: Co-producer/film director; Chanda, Redtail, Daranda, Tule, Kaila (The Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe)

Food menu

Food: charcuterie, crudite, fruit platter, turkey sandwich platter, veggie sandwich platter, hummus trio, caesar salad, four-cheese pizza, meat lovers pizza, margarita pizza, coconut shrimp, mini ahi poke, beef empanadas, chicken potstickers

Dessert: cheesecake, strawberry shortcake, German chocolate cake

Beverages: coffee, herbal tea, water, iced tea, lemonade

Add the event to your calendar

Location

Parking

Please refer to this site to find parking options (pay for a pass, use an app, use stations on campus). The closest parking structure is 12 (below). If you need help finding Scripps Cottage, use SDSU’s interactive map here.

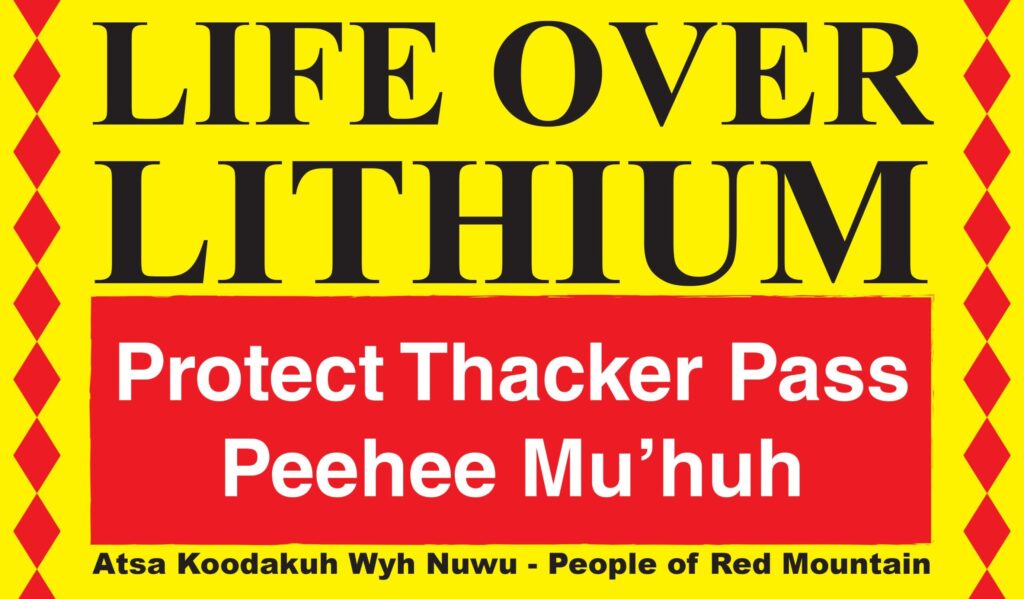

People of Red Mountain (PRM)

People of Red Mountain (PRM) call for the McDermitt Caldera’s protection, including Peehee Mu’huh – Thacker Pass. The McDermitt Caldera is located in the Northern Nevada and Southeast Oregon area, in a remote and mostly untouched part of the sagebrush steppe. It is important to note that the sagebrush steppe is declining in millions of acres per year due to human development which is another reason to preserve the Caldera. This place is the ancestral homelands of the Paiute, Shoshone, Bannock, and along with other tribes who have all occupied this landscape since time immemorial. The places around and in the McDermitt Caldera are significant to everyone who calls it home. Like Peehee Mu’huh – Thacker Pass and Kootsoo Na’a – Disaster Peak holds native peoples’ first foods, traditional medicines, pristine sagebrush habitat, dark skies, an abundance of animals and plants, and native peoples’ rich culture and history. They are sacred and hold spiritual values to the past, present, and future of Nuwu – People. The McDermitt Caldera should be protected from lithium mining and other natural resource extraction to preserve the knowledge for the next seven generations. PRM value the traditional and place-based knowledge that was shaped by these landscapes. PRM requests that all people respect the landscape and everything it holds too. This is how Protect McDermitt Caldera came to be.

For more information about their cause, please refer to their webpage here.

Meet PRM!

Daranda Hinkey

Daranda is a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe and co-founder of People of Red Mountain. People of Red Mountain is a collective group of descendants of the Fort McDermitt Tribe whose role is to protect, preserve, and steward places and landscapes fundamental to tradition, knowledge, and identities as Nuwu (People) especially from harm or destruction such as Peehee Mu’huh (Thacker Pass). She graduated from Southern Oregon University with a Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science and Policy while playing basketball on the women’s team. She spent a year after graduation working for the Lomakatsi Restoration Project in Ashland, Oregon implementing traditional ecological knowledge into land management practices and leading tribal youth workforce programs. She moved to McDermitt, Nevada, in June of 2021 after learning about the proposed Lithium Mine at Thacker Pass to be more involved in protecting sacred lands and waters.

Gary McKinney

Gary McKinney is a member and spokesperson for People of Red Mountain, an Indigenous-led organization protecting sacred landscapes from Lithium Mining. Gary is a Shoshone Paiute descendant from the Duck Valley Indian Reservation in Nevada. He is a sanctioned member of the American Indian Movement of the Northern Nevada Chapter. Gary stands for the protection of Sacred Sites that belong to the original inhabitants of what is known today as the states of Nevada, Oregon, and Idaho. Settler mining industries have long occurred in Northern Nevada and have displaced and alienated many generations of Indigenous Peoples and adversely affected significant sites, places, and land/waterscapes. Gary works to protect those sacred geographies.

Day Hinkey

Day Hinkey is a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Tribe. He is also a member of People of Red Mountain, an Indigenous-led organization seeking cultural preservation and protection of sacred landscapes from lithium mining in the McDermitt Caldera. He has forever ties to the McDermitt community and the ecosystem that he has spent his entire life hunting and gathering traditional food and medicines.

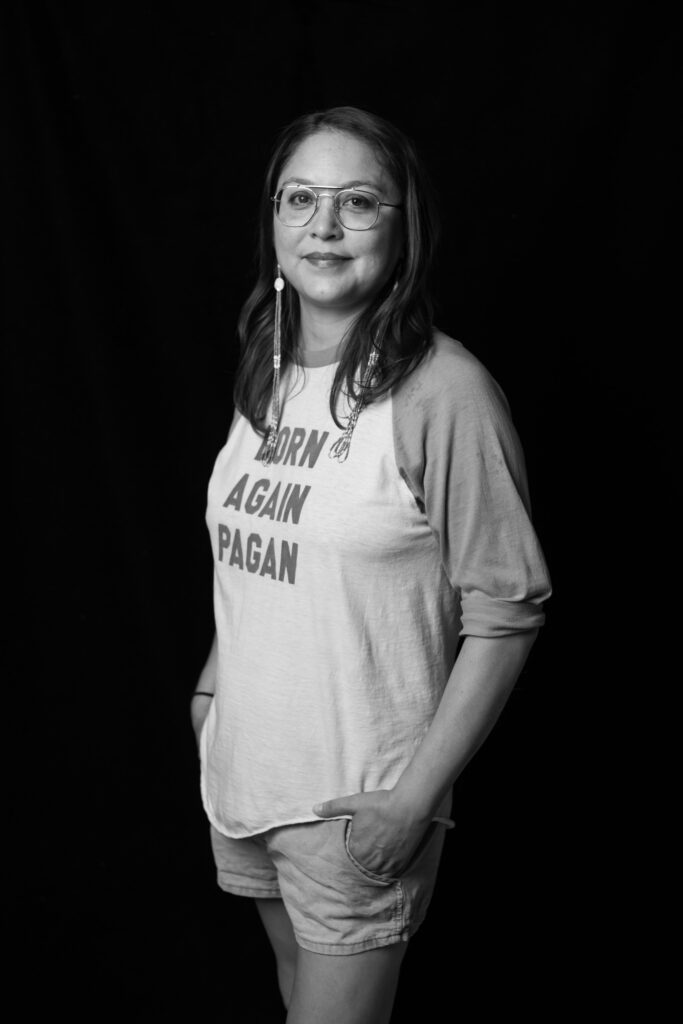

Ka’ila Farrell – Smith

Ka’ila Farrell-Smith (b. 1982) is a contemporary Klamath Modoc visual artist, writer, and activist based in Modoc Point, Oregon. The conceptual framework of her practice focuses on channeling research through a creative flow of experimentation and artistic playfulness rooted in Indigenous aesthetics and abstract formalism. Utilizing painting with wild harvested pigments and stenciling found metal detritus, her work explores space in between indigenous and western paradigms. Her work has been exhibited at Out of Sight, Museum of Northwest Art, Tacoma Art Museum, WA; Missoula Art Museum, MT and Medici Fortress, Cortona, Italy; and in Oregon she has work in the permanent collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Portland Art Museum and the Portland Building. Her solo exhibition LAND BACK was on view at the Goudi’ni Native American Art Galleries at Cal Poly Humboldt in Arcata, CA, Spring of 2023. Her work was curated in the exhibition Inherent Memory at the IAIA MoCNA in Santa Fe, NM 2023. And Ka’ila’s new work Ghosts in the Machine (2022-2023) will be on view at the Russo Lee Gallery in Portland, OR, August 2023. Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea is at The Boise Art Museum, The Utah Museum of Fine Arts, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, the Whatcom Museum, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum through 2023. The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans is curated by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and will be on view at The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC through 2023 and traveling to the New Britain Museum of Art in Connecticut through 2024. Ka’ila Farrell-Smith received a BFA in Painting from Pacific Northwest College of Art and an MFA in Contemporary Art Practices Studio from Portland State University. Farrell-Smith is a 2021 Hallie Ford Fellow and a 2019-2020 Fields Artist Fellow with Oregon Humanities.

Myron Smart

Myron Smart is a traditional knowledge keeper and descendant of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Tribe. Myron is also a member of People of Red Mountain where he fights to protect his ancestral homelands through educating communities and holding ceremonies in honor of his ancestors.

Inelda Sam

Inelda Sam is a member of the Fort McDermitt Paiute Shoshone Tribe and a member of People of Red Mountain. She advocates to preserve her traditional ways and sacred landscapes of the McDermitt Caldera from Lithium Mining.

Chanda Callao

Chanda Callao is an organizer and financial coordinator for People of Red Mountain. She is passionate about protecting the McDermitt Caldera from proposed lithium mines. Chanda has been a community member of the McDermitt Community for over 30 years.

Kumeyaay Land Acknowledgment

Prepared by Dr. Giorgio Hadi Curti

Since time immemorial, the Kumeyaay people—Ipai to the north, Tipai to the south, Kamia to the inland, and all of those who have used and continue to use the self-identifier, Diegueno, whether by active choice or colonial imposition—have been a part of the lands and waters we often call today, San Diego County.

These lands and waters have nourished, healed, protected, and been intimate and indelible parts of the familial and social of Kumeyaay for many, many generations—and continue to be today. With, in, of, and through these lands and waters, Kumeyaay have practiced familial and social relationships of stewardship, care, balance, and harmony—relational practices that live and support life always for the people.

What I have been taught by the Kumeyaay people with and for whom I work is that the depth and weight of what it means for an act, a thought, a song, a prayer, a method, an offering, an action, a practice to be for the people can only truly be glimpsed and loosely grasped when notions of “the person” and concepts of “the social” are opened up to relations and capacities that exist far before and far beyond dominant and dominating humancentric errors and blinders.

As members of the San Diego State University community and residents of the City and County of San Diego, it is imperative that those of us who are not Indigenous to these lands and waters recognize that we are contributing to a settler colonial institution, that we are, ourselves, settlers in Indigenous Kumeyaay lands, and that more often than not we are directly implicated in promulgating, promoting, and perpetuating these dominant and dominating errors and blinders—whether passively or actively.

We must both acknowledge this legacy and ongoing presence of coloniality and take ownership of the fact that each one of us has a deep obligation and weighted responsibility to actively and productively work towards restorative geographical, historical, political, cognitive, legal, educational, and social justice with and for Kumeyaay people—wherever, whenever, and however they deem appropriate.

It is thus essential that the language of land acknowledgments not be confused for the production of spaces for equitable and corrective action, or those of representational recognition mistaken for productive systemic change. If acknowledgments are to be meaningful they must be continually generative—therefore so, too, must they be accompanied by actionable institutional respect and operational structural inclusion—in perspective, policy, practice, return, and restoration—of the knowledge and political sovereignty of Kumeyaay people—and, indeed, all Native peoples—to all ancestral and familial lands and waters.

On January 20, 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 13985 on “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities through the Federal Government.” The Pueblo of Zuni responded with a government-to-government consultation letter to the Biden-Harris Administration and Office of Management and Budget on July 1, 2021, in part stating:

All lands and waters within and intersecting the borders and boundaries of the United States are Native lands and waters (see https://native-land.ca/). This basic fact must first formally be addressed, officially recognized, operationally accounted for, and serve as the basis of any honest and sincere effort at advancing equity and support for the underserved A:shiwi community and Pueblo of Zuni [and, indeed, all Native American Tribes and communities]. Recalling your own recent words this past June Mr. President, “Great nations don’t ignore their most painful moments. They don’t ignore those moments of the past. They embrace them. Great nations don’t walk away. We come to terms with the mistakes we made.”

These mistakes of settler colonial nations are as deep as they are enduring, and as prevalent as they are dispossessing and alienating—globally and locally, yesterday and today. As Potawatomi climate and environmental justice scholar Kyle Whyte has explained, Colonial- and industrial-induced climate change is in fact just one intensive manifestation of environmental change born of settler colonial societies:

Thinking about climate injustice against Indigenous peoples is less about envisioning a new future and more like the experience of déjà vu. This is because climate injustice is part of a cyclical history situated within the larger struggle of anthropogenic environmental change catalysed by colonialism, industrialism and capitalism—not three unfortunately converging courses of history [Whyte 2016:16].

Flowing through the heart and enveloping the mind of colonial, industrial, and capitalistic actors and their judgements, values, perspectives, choices, politics, and practices driving climate change are what English anthropologist Gregory Bateson identified 50 years ago as “epistemological fallacies” and “errors” of dominant—and dominating—Western systems of logic and value. Quoting Bateson:

[T]he last hundred years have demonstrated empirically that if an organism or aggregate of organisms sets to work with a focus on its own survival and thinks that that is the way to select its adaptive moves, its “progress” ends up with a destroyed environment. If the organism ends up destroying its environment, it has in fact destroyed itself [Bateson 1987:457].

And:

[Such] [e]pistemological error is all right, it’s fine, up to the point at which you create around your-self a universe in which that error becomes immanent in monstrous changes of the universe that you have created and now try to live in [Bateson 1987:485].

These epistemological fallacies and errors inform and guide not only how we frame the possible futures that climate change may or may not bring, but limit what may be included of various pasts. Mathews and Barnes address this in their introduction to an important 2016 special issue of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. They note:

[J]ust as states have sought to manipulate the past by celebrating some moments in history and silencing others, so, too, they have linked these selected pasts to particular futures. The question of the past, then, if looked at in the right way, has always also been a question about the future….

The future can be told as a story, calculated as a probability, or speculated upon as a form of potentially valuable risk…. The future … is not one but many, and those who create futures typically seek to narrow down what the future can be to a relatively limited subset of possible registers [Mathews and Barnes 2016:10-11].

I have been taught by Kumeeyaay and A:shiwi, ‘Atáaxum and Diné, Coast Salish and Chalá∙at, Lakota and Dakota, Paiute and Shoshone that to truly acknowledge Indigenous lands and waters is also to always recognize, honor, and respect both the futures and pasts of non-human and more-than-human relations that have existed from the times of the beginning of the beginning or the beginning with no beginning; these are the relationships of the air and the winds; the mists and the clouds; the soils and the minerals; the animals and the plants; the stars and the constellations—what is below and what is above. This is the life of land, air, and water. This is the capacitational life that Colonial- and industrial-induced climate change monstrously effaces and eviscerates.

Anishnaabe experience and wisdom have identified how “‘invasive’ ideologies” of settler colonial societies often manifest in and as “invasive land ethic[s]” (Reo and Ogden 2018). We can term these mutual manifestations “invasive species of thought” (Wemytewa, Curti, and Dongoske 2023 and in progress) in order to better amplify recognition and more fully name the implications of how they function in and as ongoing manifolding processes of thought and action that exceedingly work in the interests of sustaining privilege for some and perpetuating the destruction, dispossession, marginalization, and alienation of many, many others.

An etymological excavation of the term “species” reveals its root to be the Latin specere, an inflection of specio, meaning to “observe,” “watch,” or “look at.” As this suggests, considerations of what species are exist as culturally imbued constructions cataloguing, categorizing, and classifying complex formational differences of the life of the world. Where and when such categorizational schemes become invasive is in their deployments that confuse abstractions and fictions of understanding for a singular Reality beholden to narrow and limited Western notions of valid knowledge production, linear time, geometrized space, and their attendant economic, developmental, and capitalistic values that reify and rationalize devastation of places, land- and water-scapes, social relationships of reciprocity, and capacities for health and wellbeing for a multitude of peoples—human, non-human, and more-than-human alike. These are the invasive species of thought and action that have brought to all of us—and brought all of us to—the increasing effects of industrial- and colonial-induced climate change.

Kyle Whyte and South Asian environmentalist Claude Alvares have each respectively identified how, “[a]s an environmental injustice, settler colonialism is a social process by which at least one society seeks to establish its own collective continuance at the expense of the collective continuance of one or more other societies” (Whyte 2018:136), and “Western science, [as] an associate of colonial power, … function[s] not any less brazenly and effectively: extending its hegemony by intimidation, propaganda, catechism and political force” (Alvares 2010:244). With today’s Climate Talks, we seek to perform a double movement of (re)turning the gaze on these invasive species and their processes of thought, action, and inaction while offering productive pathways to enter into restorative and just correctives of and for relational life and relational life/way systems.

Goenpul scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson (2015) has identified how Indigenous pasts and futures and the relational life/ways intimately and indelibly enfolding and enfolded by them are constrained and imposed upon by settler colonial gazes of social and governmental “white possessive logics.” She explains how these racialized logics manifest and function as:

unearned invisible assets that benefit white people in their everyday lives; they are possessions. These assets include simple things such as not having to educate white children about systemic racism for their protection and having white identity affirmed in society on a daily basis through positive representations in the media, government policies, legislation, and the education system…. Assets such as these are derived from and contribute to the normalization of white possessiveness, which remains invisible to white people in everyday practice [Moreton-Robinson 2015:97].

Within, through, and beyond mainstream Western climate policy and governance, white possessive logics and their unearned privileges are invasively “operationalized within discourses to circulate sets of meanings about ownership of the nation, as part of commonsense knowledge, decision making, and socially produced conventions” and “underpinned by an excessive desire to invest in reproducing and reaffirming the nation-state’s ownership, control, and domination” (Moreton-Robinson 2015:xii).

Through misplaced confidence in highly partial knowledge schemes built through methodologies that pretend they have no foundational philosophies and their white possessive couplings to an “ideology of manifest destiny [that] continues to be fuelled [sic] by a sense of entitled racial and religious superiority maintained through networks and relations of power and privilege” (Styres 2017:93-84), various manifestations of settler colonial domination endure through mainstream climate science policy and practice as an associate to colonial power to elide considerations and undermine capacities of and for resilience and collective continuance of Indigenous peoples. The epistemological and ontological grounding of these white possessive logics is one that continually “separates and isolates and mistakes labeling and identification for knowledge” (Deloria and Wildcat 2001:133) and “superimpose[s] on nature … a [mathematical and geometrical] grid … like the land survey system…. These units, in turn, are used as the basis for dealing with the land, but they are not part of the nature of the land” (Little Bear 2000:ix). While the invasive racialized logics and species of thought underpinning these enduring injustices are omnipresent in settler colonial societies, their operations are often concomitantly unidentified and unnamed in both their settler colonial governmental and academic possessive deployments (Moreton-Robinson 2015:xxiii).

When promulgating, promoting, and perpetuating epistemological errors driving climate change, and the invasive species of thought attempting to address sustainability through unsustainable epistemologies and valuations, our institutions become perverse—and when enabling these institutional and structural monstrosities—whether passively or actively—we ourselves become monstrous. This is perhaps why in 2020 McGregor et al. took the position that:

Indigenous environmental justice (IEJ) is required in order to address [both] the challenges of the ecological crisis as well the various forms of violence and injustices experienced specifically by Indigenous peoples. This must be grounded in Indigenous philosophies, ontologies, and epistemologies in order to reflect Indigenous conceptions of what constitutes justice [McGregor et al. 2020:35].

The lesson then—if we are to become worthy to the challenges of today’s Climate Talks—is to begin to come to know, from the deep time and deep space knowledges, sciences, and wisdoms that formed and grew together with the lands and waters of what we often call today “the United States of America”, how to start to find just pathways to (re)build circuits for correctives to the epistemological errors and invasive species of thought that continue to drive our dominant modes of knowledge production, evaluation, and valuation—of pasts and futures; scientific, philosophical, economic, or otherwise—to become less monstrous in thought and action. You, the audience, are the future climate scientists and the present and future decision-makers. There are many more possibilities for inclusive, productive, balanced, collective, restorative, and generative pasts and futures out there for the people than what your algorithms, models, and projections commonly tell.

Check out last year’s event!

Watch the recording from last year

Your planning team

A special shout-out to our planning team (pictured below) for putting this event together! Also Kristen Monteverde for her feedback and support throughout this process. A special thanks to Giorgio H. Curti for his years of support and guidance, which led to the many invaluable connections GGSA has made. This event is funded by the San Diego State University Student Success Fee.

Questions and/or comments?

Email Corrie Monteverde at cmonteverde@sdsu.edu or leave a comment in our ‘Contact Us’ tab.